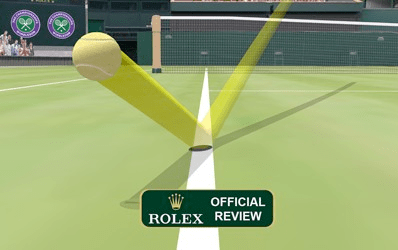

If you’re watching US Open tennis, you’ll notice that there are no line judges anymore. Almost every officiating call is made by the Hawk-Eye system. It’s used in a number of other sports, too, but let’s focus on tennis.

There’s a really good reason for using Hawk-Eye: human line judges make mistakes. Big mistakes. Sometimes mistakes that seem particularly biased against certain players. In a 2004 match, multiple egregiously bad calls were made against Serena Williams. Viewers at home who saw the slow-motion replay could easily see how wrong the calls were, and it wasn’t close. John “you cannot be serious” McEnroe called for Hawk-Eye on the spot, during the broadcast.

Initially, Hawk-Eye was used as a backup – a player could challenge a human call and have Hawk-Eye overturn it. Today, at the US Open, Hawk-Eye makes all the decisions, and players cannot appeal.

But here’s the thing – are we sure that Hawk-Eye always gets it right? In general, when you average out all the calls, Hawk-Eye is, without a doubt, better than a human line judge making a split-second decision. But can it make mistakes?

Of course Hawk-Eye can make mistakes. It’s a computerized system with bugs, like any computerized system, and it can fail in small and large ways. There was a clear malfunction in Miami 5 months ago where the Hawk-Eye rendering showed an improbable ball angle and likely incorrect call, which almost certainly affected the outcome of the match.

Most importantly, like any computerized system making a judgment call on physical evidence, Hawk-Eye needs calibration to know where the lines are. And that calibration is, of course, done by humans, and could be wrong, or the calibration could drift after a few matches.

So how do we fix this? Do we get rid of Hawk-Eye? That doesn’t seem helpful, since we know that human line judges make so many mistakes. Do we go back to human line judges with occasional challenges adjudicated by Hawk-Eye? Maybe. But that gets things backwards, since we know that Hawk-Eye is going to get it right 99.99% of the time, and humans simply can’t match that.

Instead, how about we learn from American voting machines? American voting machines read more than 150 million balllots per election. They get things right almost all the time. And they certainly do a heck of a lot better than humans counting votes. But sometimes, they can get things wrong. Maybe a mis-calibration. Maybe some dust obstructs the ballot scanner.

Many states in the US check their voting machines by running statistical post-election audits – a sample of paper ballots is selected and those ballots are verified, slowly and by hand, against their machine interpretation. Too many discrepancies, and we escalate to looking at more ballots, just in case a machine error might have affected the outcome. This is very rare – the machines almost always get it right. But on that rare occasion where they get it wrong, having an escalation path is critical.

This is the right man/machine collaboration – use machines to make a lot of decisions very quickly, and escalate to humans for a small sample where you can take your time to review every angle.

We should apply the same idea to line judges at the US Open. Use Hawk-Eye to make initial decisions, but give the chair umpire and possibly the players the right to challenge the call, which then brings up the original video stream of the shot, not interpreted by Hawk-Eye, leaving it to be reviewed by the chair umpire.

Just like voting machines + post-election human audits are the best of both worlds, Hawk-Eye + challenges & human override can help make US open calls much more consistent and fair while also controlling for the rare case where a malfunction of the technology should yield to a slow human review.

You must be logged in to post a comment.